Fongers

Without the ability to mass-produce or invest in expensive equipment, competing on price and volume was difficult. Wim Jr. faced growing frustration over his struggle to secure suitable terms with a manufacturing partner. This changed in 1961 when he entered into a deal with the giant Fongers, makers of the finest traditional Dutch bicycles. Fongers was eager to explore new markets yet hesitant to sully their brand with racing frames, which they considered too blue collar. However, RIH’s reputation in cycling provided the perfect opportunity for cooperation.

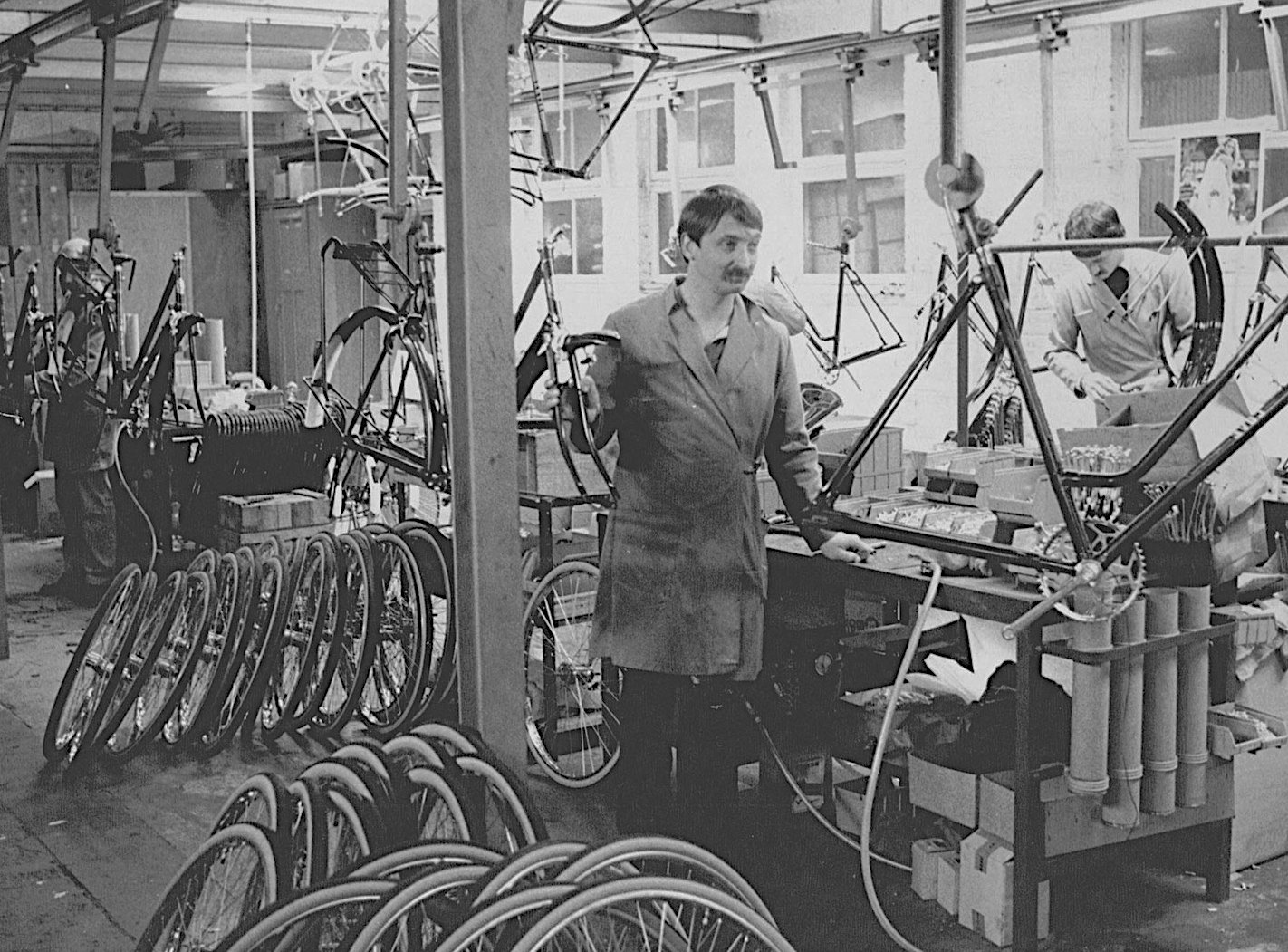

Fongers dedicated a separate production line at their Groningen factory where Bustraan personally trained the workers. They made RIHs in small series and distributed them in bike shops across the country. To boost brand visibility they also sponsored a Fongers-RIH racing team. The arrangement provided income, increased availability, and helped manage the growing waiting list.

Production continued until 1970 when Batavus acquired Fongers. Unfortunately, Batavus shuttered the Fongers factory the following year. Wim Jr. had to find another partner, lamenting that, “they have big machines that I cannot afford.”

Gradually the Dutch bicycle manufacturing market consolidated. Besides Fongers, by mid-decade Batuvus acquired Phoenix, Germaan, and Magneet. Gazelle gobbled up Locomotief, Juncker, and Simplex. This meant fewer domestic partnership opportunities for RIH.

Russian connection

The 1960s were also RIH’s most productive racing decade: 25 titles. RIH was no longer just a Dutch phenomenon. Russian Olympian Stanislav Moskvin ordered a RIH and won a championship race on it.

The brand was already known for its robust, uniquely-dimensioned stayer frames, attracting top talent like Georgian sprinter Omar Pkhakadze, who had his oversized frame custom-built by Bustraan.

The decade witnessed Eastern Bloc countries, especially the Soviet Union, rising to prominence in Olympic cycling events. RIH played a significant role by equipping both the Russian men’s and women’s Olympic teams. In 1967 Limburgs Dagblad reported a significant Soviet order of 25 frames. Throughout this era Wim Jr. served as an informal advisor to the team, making a dozen trips to Moscow. His efforts were bolstered by Mrs. Bustraan’s fluency in the languages of her youth. Notably, Russian women clinched eight of the 25 championships during this successful period for RIH.

Watch Omar Pkhakadze compete against Igor Tselavalnikov to a photo finish in a short jazzy Russian-language video “двое на треке” or “Two on the Track.” The film is dated 1970; RIH built bikes for Omar and Igor in both 1967 and 1968.

Unique designs

In 1969 De Tijd noted Wim Jr.’s missed opportunity to independently grow the business. He countered, “ah, sir, being rich isn’t so important…I have black hands, and if your hands aren’t black, then you aren’t truly rich. It means you’ve let others do the work.”

By 1971 the 56-year-old artisan Wim Jr. expressed his desire to transition from being a craftsman to selling his bicycle designs to a factory for mass production. “I see myself as a craftsman, not an organizer,” he shared with Het Parool. “I want a factory to produce my bicycle designs in series, but always under my supervision.” Despite his efforts, Wim Jr. admitted that success was elusive. “What I see entering the market is appalling, yet when I offer my designs, there’s little interest. I don’t understand. With a large factory backing my models, you could earn gold.”

That same year, Wim Jr. discussed a potential partnership with Gazelle in De Telegraaf. Nothing came of it.

The reality of transferring RIH’s unique bicycle designs to mass production raises intriguing questions. While orderly, the workshop’s manufacturing processes had remained largely unchanged for the past 50 years. Upstairs, the workshop was cluttered with boxes of bottom brackets, lugs, and fork crowns. As Wim Jr. and Wim crafted their frames, they relied on their expertise to calculate and remember the precise angles and tube lengths. For these seasoned craftsmen, achieving the perfect “bike fit” was an intuitive art honed through years of practice. “It’s all about experience and feel,” Wim explained.

Cové

Family operated Cové Rijwielenfabriek was founded in 1945 by Coen Verberkt. Located in Venlo in the southern province of Limburg, Cové agreed to produce replica RIHs in 1972. In this way RIH profited from bike boom demand and continued building custom frames. The Westerstraat shop even sold the replicas next to the real RIHs.

Cové ceased production of road or racing sport bikes by 1995 after a twenty-two year production run. They moved on to city bikes and, later, electric bikes. Cové eventually changed its name to RIH-Cové. Today they remain a small independent company not gobbled up by one of the global giants.

The third generation

“My father built bikes until he died, but I’m not doing that,” Wim Bustraan Jr. told De Tijd. On January 1, 1973, ownership of the Westerstraat shop passed to 35-year old Wim van der Kaaij. Bustraan, 58 at the time, continued at the shop in a reduced capacity. This gave him time to pursue his second passion: fishing. He remained the public face of RIH even though van der Kaaij was the owner. Ger Hermans began working for van der Kaaij around this time. Ger worked there for the next eighteen years.

Dutch Masters

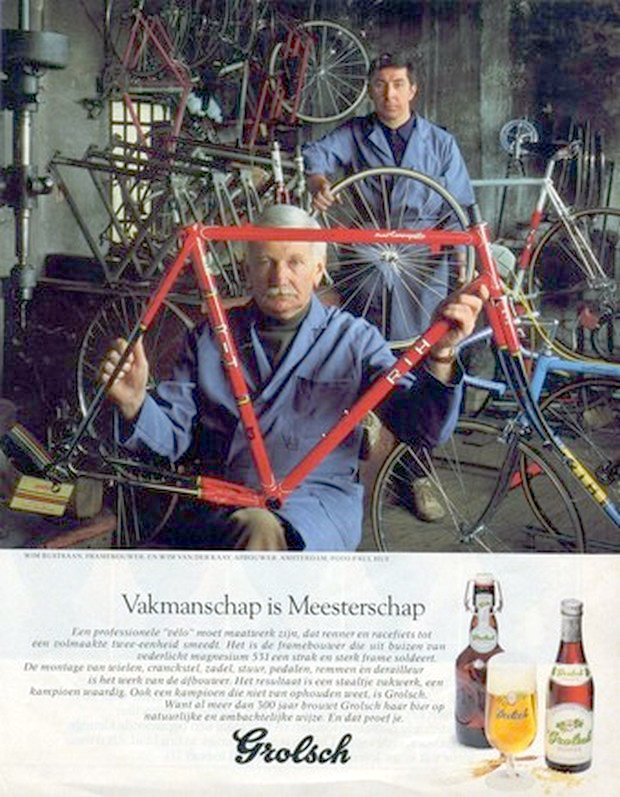

During this time brewer Grolsch featured RIH in their long-running Vakmanschap is Meesterschap (Craftsmanship is Mastery) advertising series. It featured contemporary Dutch masters pictured by the noted photographer Paul Huf. Two of the masters were Wim Jr. and Wim upstairs in the shop, posing together with a frame.

Wim alone was featured in a 1968 Grolsch television advertisement.

Twelve more racers won world championships on RIHs during the 70s. Notable was Hennie Kuiper’s 1972 Olympic road race breakaway gold in Munich.