Attic Workshop

Severus and Anna Bustraan’s two sons, Willem Adrianus and Johannes Jacobus (Joop) Bustraan, were born in Amsterdam. Following in their father’s footsteps, they were destined to work as skilled benchmen and pipefitters at Westergasfabriek (Western Gas Works, an Amsterdam coal-to-gas enterprise).

Willem was already a 27-year-old amateur cyclist by 1915. Meanwhile, his 18 year old brother Joop had recently shifted his interest from football to a fascination with cycling. The heavy Dutch utilitarian bicycles of the time were not intended for racing. Undeterred, the brothers transformed a Kinkerbuurt attic into a makeshift workshop dedicated to crafting racing bicycle frames from repurposed tubes. Through diligence they learned new methods, made mistakes, and generally honed their skills, gaining a strong word-of-mouth reputation in the cycling community.

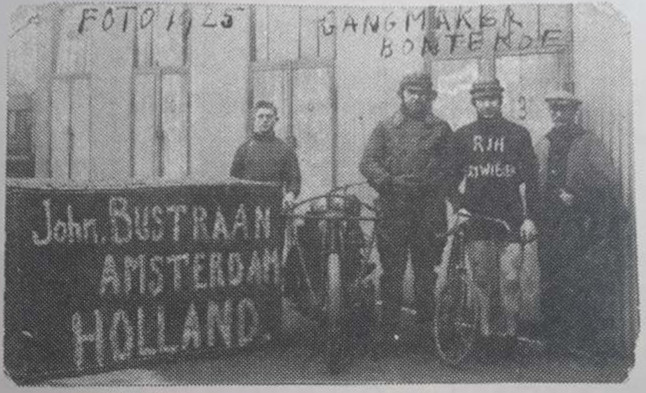

They opened a small frame building and repair shop on March 21, 1921. It was in the busy Jordaan district at Eerste Boomdwarsstraat 9. They named their bikes RIH.

Differentiating the Willems

It’s darn confusing when all the main characters share the name Willem. To simplify this, here’s how they’ll be distinguished:

- Willem – Refers to Willem Adrianus Bustraan (1888-1955)

- Wim Jr. – His son, also named Willem Adrianus Bustraan (1915-1983)

- Wim – Refers to Willem van der Kaaij (1937-2014), the successor

Willem Bustraan

Upstairs tacking, filing, and brazing

Willem grew further into his role as a bicycle frame builder while his younger brother explored a wide range of interests. The craft has been described as “not much more than super-accurate plumbing” but with the stipulation that “the skill comes in handling the materials, controlling the heat, judging when the molten brass has penetrated the entire joint and being able to estimate and minimize the effects of expansion and contraction.”

The well-worn wooden steps leading up to the second floor (sorry, eerste verdieping) workshop are mentioned innumerable times in the sources. Inside, frames, wheels, and forks were suspended from the ceiling. In this compact workspace, Willem meticulously measured, tacked, filed, brazed, and polished each frame. A solitary figure with a gruff demeanor and a temper, Willem was the epitome of a master frame builder. His true language was spoken through the torch and the steel he wielded.

Meticulous

Willem’s perfectionist nature was evident in every aspect of his work. When he was brazing no one was allowed to ascend the stairs, as he couldn’t tolerate even the slightest draft. This sensitivity was crucial because the temperature of a brazed lugged joint is vital; any sudden change can compromise its integrity. To ensure he could solder frames undisturbed, Willem sometimes opened the shop only in the afternoons, declaring, “continually disturbing me does not improve the quality of the weld seams.” His focus was unwavering.

Willem was the pillar of the family business, even as his brother Joop explored a wide array of interests beyond frame building. Following Willem’s unexpected death at 67, the legacy was passed to his son Wim Jr.

Joop Bustraan

Sprinting and tandems

Joop started cycling at 18 but was not fond of training for competitions. Cycling during his time came with challenges—poor roads, lack of lighting, and strict regulations. He complained, “we were not allowed to ride with bare arms and legs.” He wasn’t joking; a 1905 law only permitted the exposure of a cyclist’s hands and heads. Moreover, “even top riders had to have day jobs.”

Joop’s racing achievements began appearing in the Nederlandsche Sport magazine in 1922, and by the next year he had become a professional sprinter. Paired with Frans de Vreng, a 1920 Olympic medalist, Joop became part of an almost unbeatable tandem team in 1924 and 1925. RIH was known to build tandem bicycles throughout its history—it is possible this was the genesis.

In his early thirties Joop moved into motor-paced racing, driving a pacing motorcycle rather than a bicycle. The sport was particularly popular with more than 160 open velodromes in the country, usually made of wood, concrete, or grass. The excitement of motor-paced racing held its own unique appeal. Over the years Joop excelled in this high speed sport and became a sought after pacer among riders.

Earning appearance fees and a portion of prize monies, it was potentially more lucrative than his association with the RIH workshop. The danger of the job combined with the necessary skills made pacers a valuable asset and justified a solid income. A skilled professional like a pacer provided a good living in the nineteen thirties, perhaps better than the irregular and unpredictable income of a small frame building shop split between two brothers.

At fifty-nine Joop decided to slow down and transitioned to a new role as a race judge, continuing his passion for the sport from a different perspective.

Gregarious storyteller

Joop’s outgoing personality wasn’t keen on isolating himself in the upstairs workshop. By 1953 he had formally parted ways with the shop. As with many of his peers, Joop invested his earnings into ventures that would secure his financial independence. He capitalized on his sports fame—stemming from his personal victories and his connection with RIH—by successfully managing two pubs, one located on the Rokin and another on Martelaarsgracht.

After buying a café in Kadijksplein, Joop admitted to De Telegraaf, “I didn’t know how to pour a beer. I learned it in one night, but by the end of the evening I couldn’t quite remember how.” Henk Faanhof, a cyclist and Jordaan friend, noted that Joop was also a talented pianist. He led a dance trio and even made appearances on radio broadcasts.

At 70 years old, Joop reflected, saying, “After spending 12 years as a rider and 23 years as a pacer, racing remains the most cherished chapter of my life.”

Wim Bustraan, Jr

Willem Bustraan died suddenly in mid-1955, leaving the family business in the hands of his son Wim Jr. At 40 years old, Wim Jr. had been immersed in the frame building trade since his teenage years. Recognizing he could not meet demand alone he enlisted the support of 18-year-old Wim van der Kaaij as his right-hand man.

Racing successes boost demand

RIH began sponsoring road racing teams in the 1950’s, usually collaborating with co-sponsors like tire makers Radium and Vredestein. RIH crafted high-quality frames for both amateur and professional cyclists, accommodating individual athletes and full teams alike. Notably, half of RIH’s world and Olympic titles were achieved during Wim Jr.’s time.

As the cycling sport evolved, the business landscape began to change. Some racing teams secured exclusive contracts with equipment sponsors while some frame builders expanded into medium-sized suppliers. Others sold their brand names and cashed out. In response, Wim Jr. broadened RIH’s production capabilities through licensing agreements with companies like Fongers and Cové, ensuring that the Westerstraat shop could continue handcrafting custom racing bikes.

Small workshop, international reputation

Beginning in the 1960s RIH began crafting bicycle frames for the Russian national team, with Wim Jr.’s Ukrainian-born wife Angelina acting as a translator. This foreign venture then attracted orders from South Africa, Australia, Norway, Japan, Canada, and the United States.

Wim Jr. decided to slow down in 1973, passing the business to van der Kaaij. While he remained the public face of RIH, his frame production decreased. On the other hand, he found more time to enjoy his favorite pastime: fishing.

Regarded by many as the dean of the Amsterdam frame builders, Wim Jr. passed away in 1983.

Wim van der Kaaij

Fish story

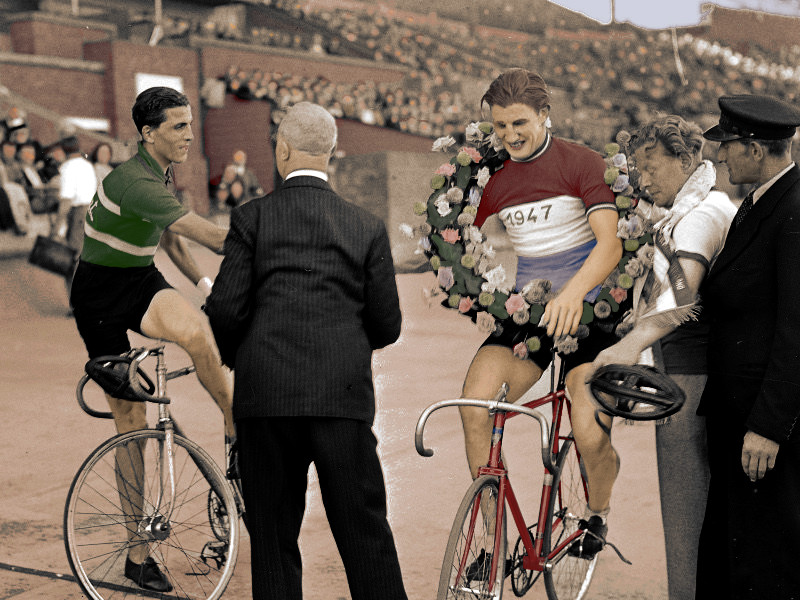

Gerrit Schulte stood out among other RIH racers. A devoted friend, he helped the family with food during the war. In 1948 he triumphed over the legendary Fausto Coppi to win the World Pursuit Championship. It happened in Amsterdam’s Olympic Stadium making it the talk of the city. The victory gave another boost to RIH’s wider post-war reputation.

The following Monday afternoon, eleven-year-old Wim van der Kaaij wandered into the local shop to purchase handlebar tape. Just then, the legendary cyclist Schulte entered. Seeing the young Wim, Joop discreetly pulled him aside and handed him a few guilders, instructing him to bring back some celebratory herring from Stubbe’s haringhuis. As van der Kaaij later recounted, “My very first task was fetching herring for Schulte…I was captured by this whole atmosphere of cycle racing and craftsmanship and I found my destiny.” This marked his introduction to cycling’s excitement, foreshadowing a promising future in the sport.

Wim van der Kaaij started his journey at the RIH bicycle shop by initially sweeping floors and fetching groceries. As racing clients frequented the store Wim took the opportunity to get to know them. He also accompanied Oom Joop during motor-paced races, learning about the racing sport. “I immediately became part of the family.”

Apart from a break for trade school, Wim lived his entire life at RIH. Following Willem’s 1955 passing, Wim Jr. hired Wim van der Kaaij. Eighteen years later Wim owned RIH.

Wim became recognized as a master builder in his own right. Just as Wim Jr had hired Wim, Wim soon hired and then mentored Ger Hermans for 18 years in the Westerstraat shop. Hermans opened his own shop in Amsterdam in 1994 and made Ger-branded bikes.

Caring for the next generation, preserving the sport

RIH built many track bikes. To help track racing endure, Wim was instrumental in founding the Amsterdamse Baanwielerschool (Amsterdam Track Cycling School). He provided the bicycles for the classes. His wife Rie worked the cash box and sold candy every race Friday. Always active, outside of cycling Wim and Rie were long-time competitive ballroom dancers.

A wonderful 2009 short film featuring Wim was produced by Meik de Swaan and David Dijkhoff. Wim is speaking while building a bike in the Westerstraat workshop. At the time of filming RIH bikes had been built in that space for 70 years.